Manchester, From the Inside: Al Baker’s Archive of a Disappearing City

Manchester changed fast.

Buildings went. Venues went. Whole areas got flattened and rebuilt into something smoother. But the images didn’t move. They sat there like proof — of who was in the room, what people wore, how close you could stand to the DJ and what the city looked like when art had space to grow without permission.

Al Baker arrived in Manchester as a young lad from Grimsby in the winter of 1987. He came with mates in a band, found himself in Longsight, and — one by one — watched everyone drift back home. He stayed.

This conversation follows the thread from those early days through Hulme, graffiti jams, basement parties, and the club nights that shaped the city’s underground — not as nostalgia, but as documentation. Before social media turned every night into a performance, Al was there with a camera as part of the room itself — trusted, familiar, and close enough to capture things as they actually were.

Al Baker photography

Arrival

Do you remember the moment you arrived in Manchester for the first time?

What did the city feel like to a young lad from Grimsby — the streets, the characters, the energy?

I came to Manchester with mates who were in a band. Xmas 1987 they told me their plan to move to Manchester. I was devastated, until they said there was a spare room going in the house & did I want to tag along. The band didn’t last and, one by one, they all drifted back. But I’m still here. I just had to figure out why I was here, that took me a while.

We lived in a terrace in Longsight, in among student houses, Indian families, Irish pubs. Where we grew up was white & conservative. I don’t mean politically, it was a Labour town for years, but it wasn’t multicultural. I loved 2-Tone but there were more black faces on my bedroom wall than on my street. At my 1st Moss Side carnival I thought I’d arrived in heaven, Caribbean cook-out & sound-systems; at the 2nd I saw my 1st shotgun. There were foodstuffs I didn’t recognise on Moss Side & Longsight markets; the wonderful smells of Curry Mile.

Being on the dole we spent a lot of time entertaining ourselves, but Longsight had an excellent record library, I think it was 20p per album per week, so I’d come home with a stack of dub or jazz records for a pound. I’d never have known where to start otherwise!

Hulme, Manchester

There was the Cornerhouse & the Aaben in Hulme to check out European art-house cinema. I discovered poets like Allen Ginsberg & Robert Creeley; Jack Kerouac, Charles Bukowski, William Burroughs; playwrights like Alan Bennett, David Mercer, Harold Pinter. I’d go Central Library, get an armful of books, and spend the whole day in the Alasia Snack Bar, a Greek greasy-spoon café run by Papa Thomas Papathomas. It was a real 1970s time-capsule, unchanged in years, full of old characters. They seemed to sit in there all day too. I soon realised it was because Papa gave unsold food away at the end of the day. You could sit for hours and you only ever paid before you left.

It had a dodgy basement club beneath called Papa’s Club which became The Roadhouse. But someone was pressuring him to sell up & he refused, so he got shot. Not long after that he retired. I miss that place.

After a year our house began to fall apart around us, the living room ceiling collapsed, so we moved to a big house in Withington. It had a double cellar so the band had somewhere to rehearse. It also meant that when we threw a party we had big speakers we could set up, so our neighbours loved us!

As you were

Hulme

Let’s talk about Hulme.

What was day-to-day life like in the crescents — the people, the chaos, the humour, the danger, the sense of community?

Charles Dickens wrote: ‘It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. It was the age of wisdom, the age of foolishness. It was the season of light, the season of darkness. It was the spring of hope. It was the winter of despair. We had everything before us. We had nothing before us. We were all going to heaven. We were all going direct the other way.’

(A Tale Of Two Cities, 1859)

Hulme was quite unlike anywhere I’ve ever lived, before or since. It was part of the post-war slum clearances. Old back-to-back housing was demolished and a pre-fabricated concrete ghetto took its place, with no through-roads and inter-connecting walkways between the housing blocks. ‘Streets in the sky’ they called it.

Policing the estate was difficult so they just didn’t bother. Flats were cold & damp, under floor heating didn’t work, lifts didn’t either, some flats had cockroaches. It was an eyesore & embarrassment to the council. Families moved out, not somewhere people wanted to raise their kids. By 1984 MCC stopped trying to collect rent.

The people who took advantage & moved in were mostly young people looking for cheap or non-existent rent: anarchists, bands, punks, Rastas, students, travellers, and drug addicts. I made friends then whom I still hold dear to this day. It was like its own inner-city village, separate from Manchester yet self-contained; a tale of two cities.

Hulme

Hulme moments

Hulme was full of stories — free parties, squat raves, cellar sessions…

Is there one moment or photo from that period that still sits vividly in your mind?

My friend Speedy Bob once caught 3 scallies trying to break into his lock-up garage. He chased them down, caught one & held him by the throat. He demanded “What’s the name of your friends?” When he gave them up Bob slapped him really hard across the face & said “Never grass on your mates!” Pure class, you can’t write that shit.

Bonsall Street

Do you remember the gas explosion in the Bullrings?

Where were you that day — and did events like that change how you viewed the estate?

Not the Bullrings, it was Bonsall Street, February ‘96. I was on my Redbrick flat balcony. I nearly fell off! It was physical, like a wave. BOOM! I actually saw the air move. I saw a black column of smoke, grabbed my camera & ran from the flat.

Smack-heads had stolen copper piping from the flat below but, because they’re thoughtless c*nts, had not turned off the gas. Poor old Gwen Harding, in her 70s, her flat destroyed, walls blown out in an instant.

While she was in hospital there was the annual Punx Picnic party and a graffiti jam happening. A plastic bucket got passed around, and when it was full we took it to the Sir Henry Royce pub because we knew they had a safe. When she came out of hospital there was money for her, I forget how much. She’s passed away now, bless her, but her daughter is still in touch. Manchester punk band The Autonomads used that photograph as their album cover in 2014.

Bonsall Street, Hulme. After the gas explosion

Graffiti and SMEAR

You documented some of the most important graffiti writers and SMEAR Jams of the 90s.

What drew you to the graffiti scene — and which writers or crews did you rate or connect with most?

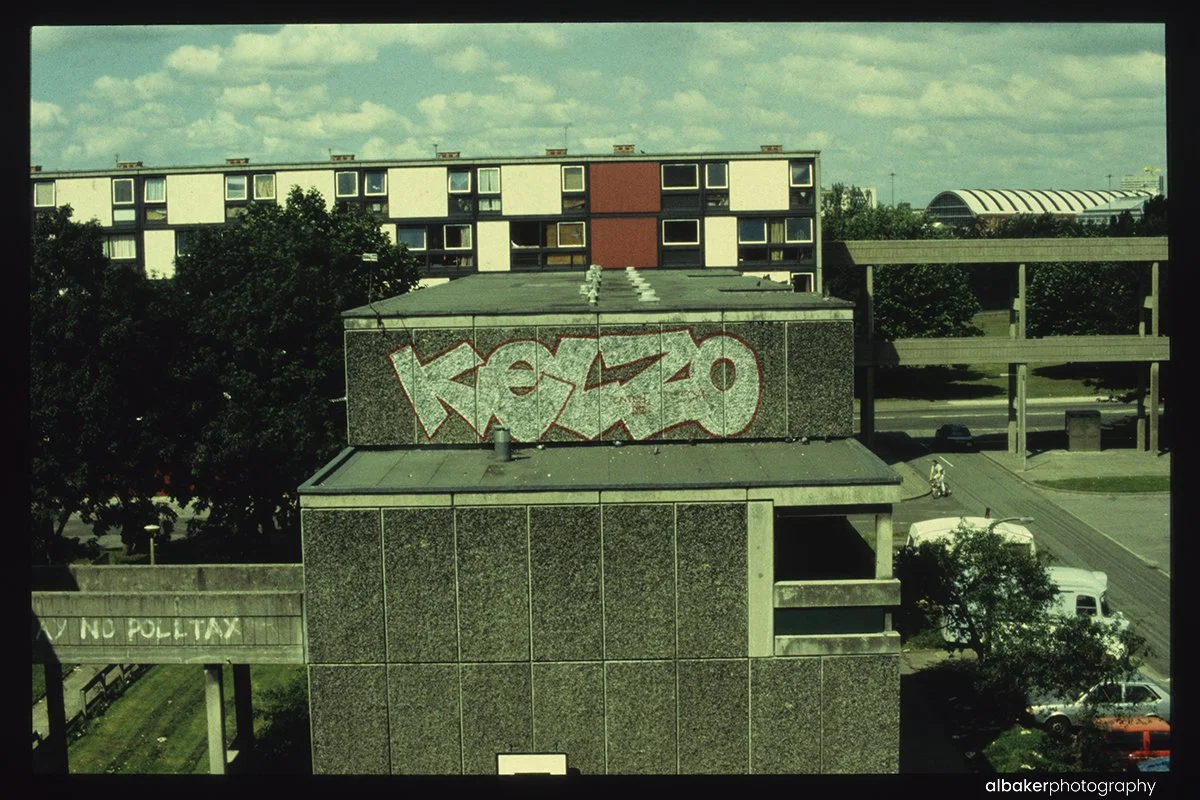

Not long after I moved in the local ICA crew started to paint the estate, on shop shutters & garage doors. Kelzo, Tags, Arise, Karl123, They turned Hulme into an ever-changing gallery.

Graf artists usually work illegally, at night. In Hulme they painted during the day, out in the open. Everyone liked it, not just hip-hop kids. It brought some psychedelic colour to a drab environment. People preferred it to the usual vandalism, declarations of love or football teams. Once one shutter was painted another shop would ask them to do theirs. There’s a photographic print of my Robert Lizar shutter in each of their 3 solicitor offices today.

When an area was earmarked for demolition the ICA would move in, begin a new Hall of Fame. I documented these pieces but realised that ‘context is everything’ so stepped back and took photos with these derelict buildings.

Back then Kelzo was King. He organised all the SMEAR Jams. Arise was a maniac, he’d tag DIE DIE DIE over & over on bus windows. Karl 123 had a very not-hip-hop style. Zed-9 was amazing, the flow of his lettering was beautiful. He got badly electrocuted painting in a train yard one night from overhead cables and is very lucky to still be with us.

Kelzo, Manchester

Early underground nights

Around the same time you were documenting Hulme, you were also inside early nights like Counter Culture, Planet K, and Electroboogieland.

What was that era of Manchester nightlife like — and what made it so different from what came later?

There were great techno & jungle nights at the Russell / PSV (Pollen, Darkhouse) and at Sankeys (Bugged Out! Guidance) The Russell Club in Hulme was where Tony Wilson first started putting on gigs in the post-punk era, which lead to Factory Records & the Hacienda.

One night at Planet K, not long after it opened, I got talking to promoter Adam Russ (Ear To The Ground). He introduced me to the owner and that night I became their resident photographer. I thought I’d photograph Manchester nightlife there for a year and maybe turn it into an exhibition or a book but I was kept busy for nearly 20 years!

Going halves

Planet K

Planet K felt like a bridge between so many worlds: hip hop, electro, breaks, graffiti kids, students, ravers…

How important was that venue to the city’s underground identity?

My mission was to cover all of their nights, and everyone who worked there, but eventually you graduate toward the music you prefer. Bouncers loved being photographed, the bar staff didn’t. I suspect some of them were signing on.

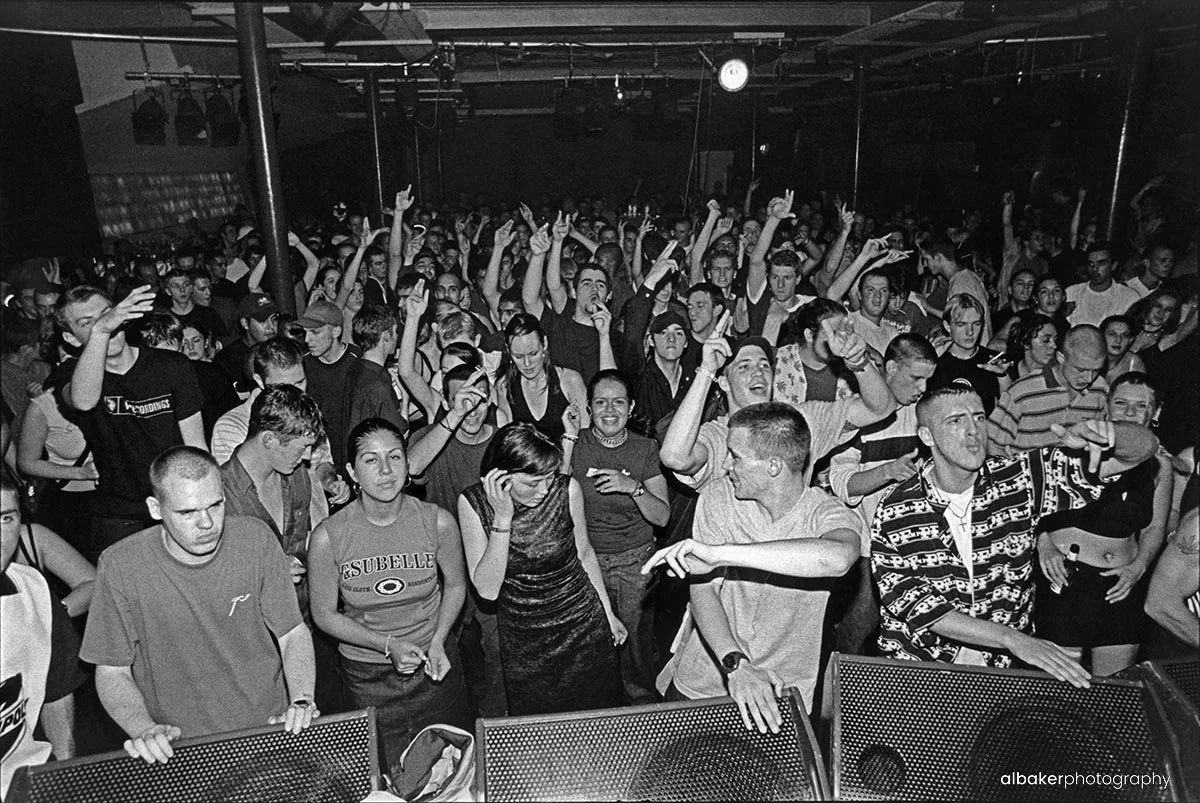

The best nights were a good mix of locals & students: Fat City & Grand Central Records ‘Counter Culture’, Mr Scruff’s ‘Keep It Unreal’, ‘Heat’ and ‘Spellbound’.

As a club it only lasted 2 years but I built my nightlife portfolio there. I could go down anytime I wanted, so sometimes I went 3 nights a week. I would check out odd bands who sounded interesting and I became a regular fixture at ‘Counter Culture’ (hip-hop) and ‘Spellbound’ (DNB). There was always more to see, more interesting for a photographer, than at straight House music nights. This is where I cut my teeth.

Then ‘Electric Chair’ moved from Saturday nights at The Roadhouse to Music Box, ‘Counter Culture’ became ‘Friends-&-Family’ and slotted in its place. Mr Scruff went to Band On the Wall, ‘Spellbound’ went to Sankeys and I went with them.

Planet K which eventually became the Mint Lounge. Spot Chimpo?

Friends-&-Family

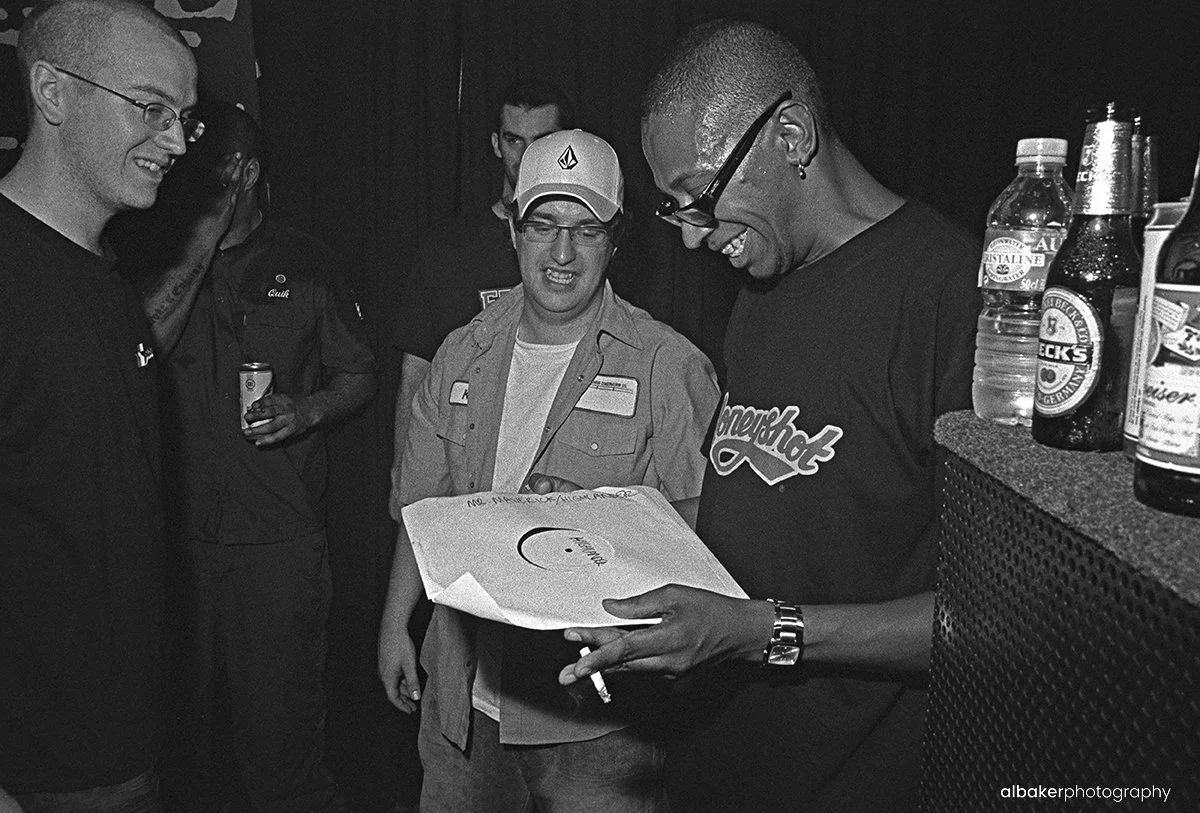

Your Friends & Family archive is incredible — Roots Manuva, Madlib, J-Rocc, Est’elle, Peanut Butter Wolf, Souls of Mischief, Daddy G and more.

What made that night so special — and how did it shape Manchester’s hip hop identity?

Friends-&-Family remains one my most favourite club nights in Manchester. They had great guests, but they also had great residents: Aim, Mark Rae, Martin Brew, Poppa Laws, Riton, Woody, MC Kwasi. The music policy was quite broad, mostly hip-hop & soul but you’d also hear disco, funk, reggae. It was never just about the classics, always a good mix of new & old music, and the atmosphere!

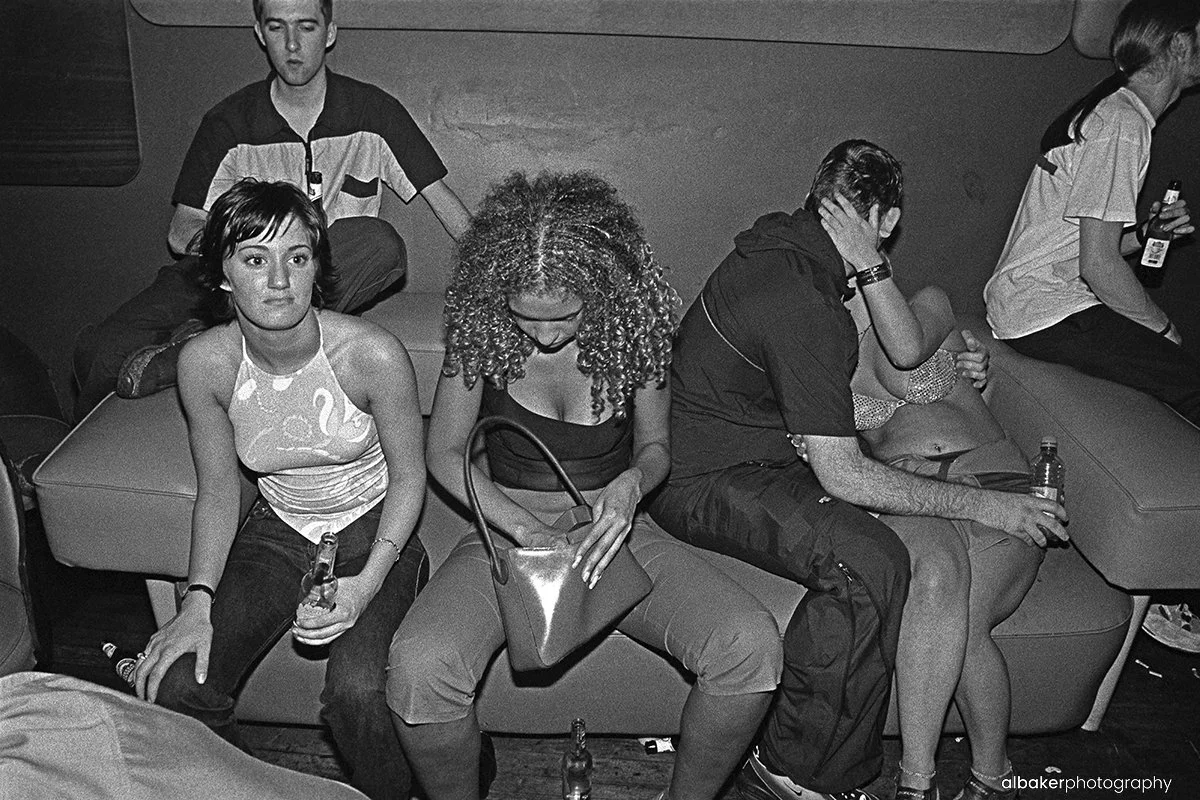

That Stones Throw Records night with Madlib, J-Rocc & Monk-One has to be one of the hottest nights I’ve ever worked. Coming in from the cold night air my camera immediately steamed up & stayed that way. There’s nothing you can do. You have to wait until the camera reaches the same temperature as the room before you can even begin. A tip for any budding nightclub photographers – don’t arrive late! Especially in February in Manchester.

Madlib at Friends and Family

My favourite night at The Roadhouse was Roots Manuva. ‘Witness’ was a UKHH crossover smash that summer. It was HUGE! You heard it EVERYWHERE! I knew he was gonna blow up. I was with an old friend in Battersea for Notting Hill Carnival that year. I saw the posters for his ‘Run Come Save Me’ tour and ran over to see where he was playing Manchester. Seeing ‘Friends-&-Family @ The Roadhouse’ on that poster was JOY! I knew I could get in, I could shoot the gig, and I knew that I’d never again see him on a stage that small. What an opportunity! A great night, I stood stage-right the whole show. After playing ‘Clockwork’ he turned to me & said “You sang that one louder than me bruv.”

Roots Manuva at The Roadhouse

Manchester artists

You also captured so many Manchester artists from across the eras — Broke ’n’ English, DRS, Strategy, Konny Kon, Bandit, Jenna G, 3rd Degree, Mark Rae, DJ Woody, Mikey Don, Tonn Piper, St Files, Marcus Intalex, Zed Bias, Virus Syndicate, and more.

What was it like photographing that community — and how did the local scene blend with the visiting US & UK acts?

Broke’n’English supported just about every visiting hop-hop act who came to town; Strategy & Jenna G at Eardrum, as well as Spellbound; Tonn at Spellbound, Metropolis, Hit-&-Run.

Jenna G and Strategy at Eardrum, Dry Bar, Oldham Street

Marcus Intalex had great residents at Soul:ution: Bane, Calibre, Dub Phizix, S.P.Y. His Soul:R label a blueprint for how to do things properly.

Hit-&-Run is another favourite night of mine, a Manchester institution. So many producers & DJs made their MCR debut at that night. It’s a proper MC school, allowing local MCs to spit on different flavours & BPMs. Levelz was a super-group born out of that night. Music made from many different pieces; dubstep, dancehall, disco, grime, hip-hop, jungle. It’s all in there. 4 DJs and 7 MCs, they never failed to put on a great live show. It was a real shame that they imploded.

What I like about the Manchester scene is a distinct lack of back-biting competition. What I saw then I still see; good people prepared to give talent a helping hand. When Manchester people see some form of success they don’t pull up the ladder & protect their new status, they use that success as a platform for others.

Broke;n;£English, Sankeys Soap

There’s 18 different producers on DRS Soul:R albums, the ‘Bun Ya’ posse-cut was like a calling card for what became Levelz. Lenzman & DRS helped break Children Of Zeus with that ‘Still Standing’ remix. In turn, they brought [KSR] forward. Sappo, Zed Bias & Dub Phizix helped young producers with studio technique & mastering.

I think it’s healthy. Whenever I feel that Manchester’s gone quiet, you know that something’s being cooked up somewhere. I remember Konny sending me early Children Of Zeus when people were scratching their heads saying “No-one’s making music like this!” like it was a bad thing, but now people use the exact same words but in a positive way.

It’s been a real pleasure to watch these people go from support act to headline act, recording artists, gigs abroad. It makes for some great nights out when the gang gathers together. Like one big, chaotic, dysfunctional family. I love it.

Jungle and DnB

When did jungle and drum & bass enter your world — and what nights defined that shift for you?

Darkhouse at the PSV, Guidance at Sankeys, Spellbound at Planet K… what stands out from those rooms?

Devious D had some issues with his Phenomenon One night in ’95: Rob Gretton (New Order manager & co-director at Factory) really wanted a Jungle night at the Hacienda, but the door-staff weren’t happy policing it. It was a ram-jam sell-out night but it never happened again.

Some friends of mine put on their own drum n bass night in ‘97 called ‘Transmission’. Da Intalex, Devious D, Durban & Sappo. MCs Akrasi, Crystalize & Trigga. Live drums by James Ford. I provided visuals. But it moved around too much to hold onto its audience. Kaleida (where Matt & Phreds is now), Cyberia, then PSV.

You have to remember that most of the doors in city-centre were run by Salford, and we had kids coming down from Moss Side, Cheetham Hill. It could get moody. You had a sense that if anything did kick off you were on your own.

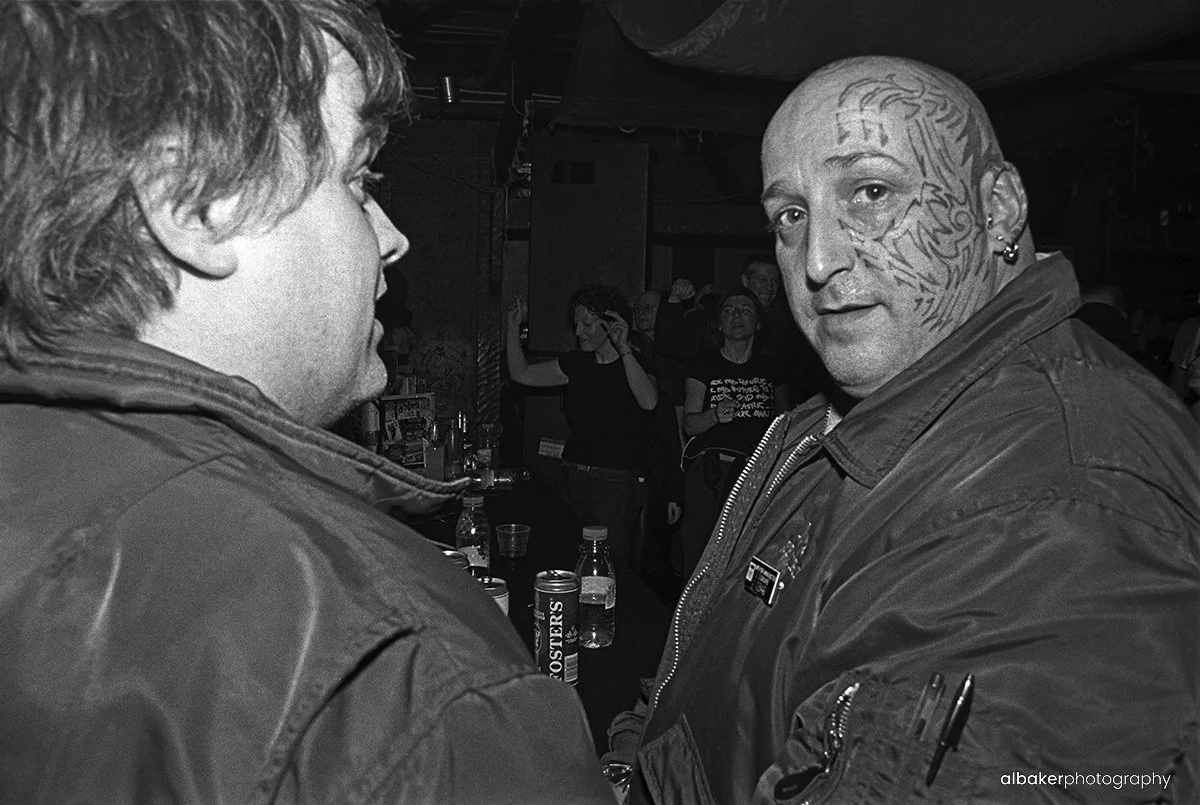

‘Twinny’, the head bouncer at Music Box, Oxford road

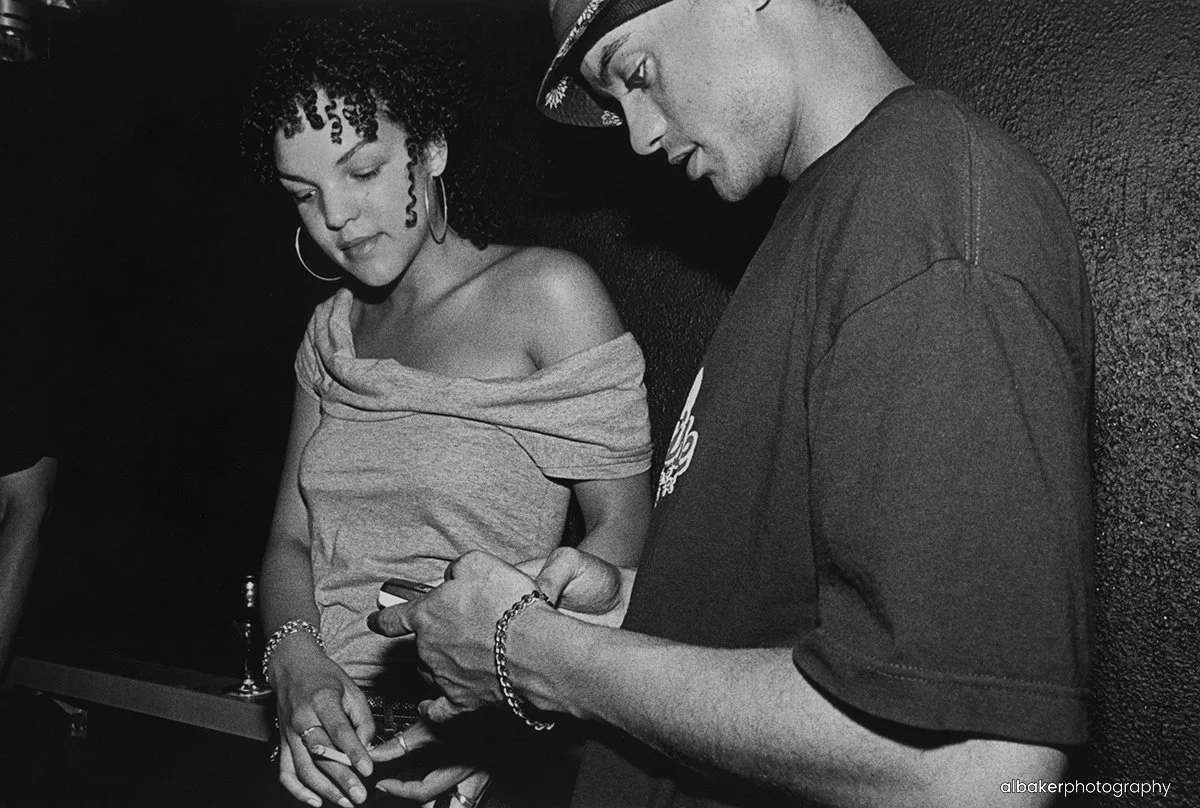

The one guy who seemed to get it right was Inki, with Spellbound. The correct mix of black/white, male/female, students/locals, live musicians alongside his DJs. There were a few characters, some serious heads dotted about, but everyone there seemed to respect what he was doing, I never saw any trouble.

Soon there were lots of other great nights too: Audiosalad, Gutterfunk, Hit-&-Run, Metropolis, Platoon, Rollin’ Sounds, Soul:ution.

Early DnB energy

You documented moments that many younger DnB fans will have never seen.

What was the energy in those early DnB rooms like compared to what we see today?

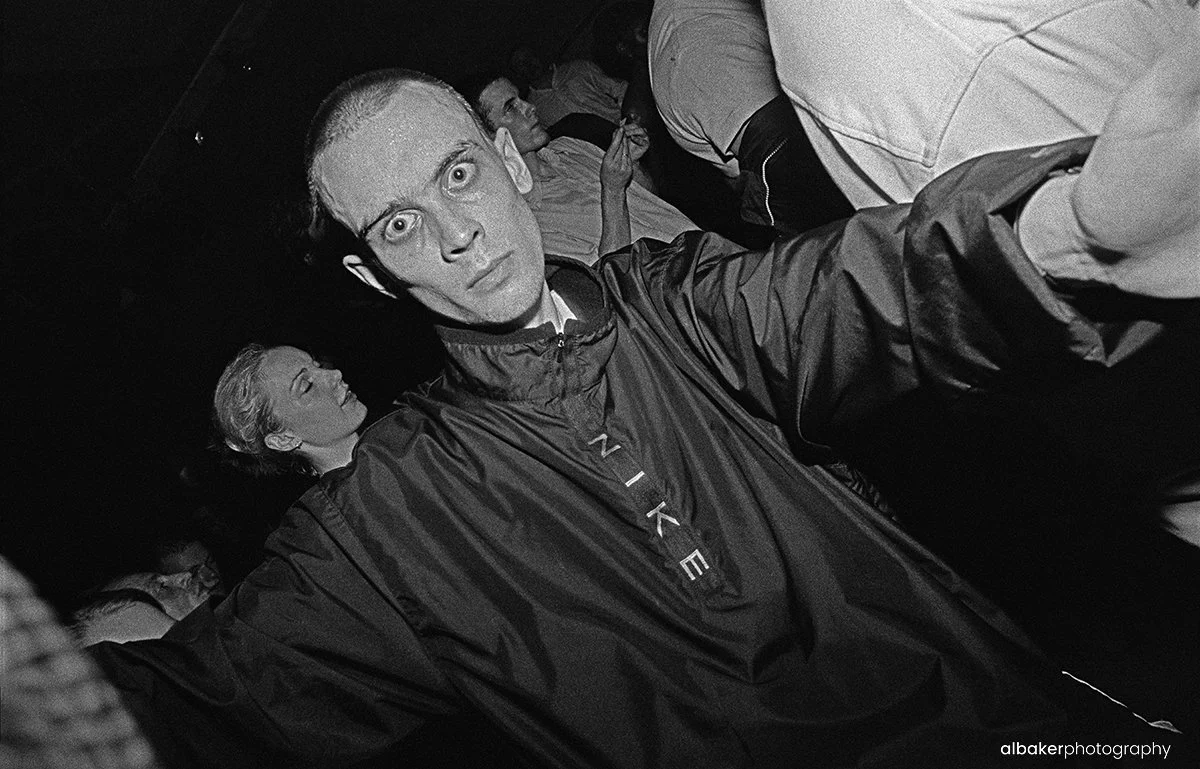

Darkhouse at the PSV in 95 was pretty wild! It was a West Indian club for bus drivers, (PSV stands for Public Service Vehicle). There might be a rave going on downstairs but upstairs was old-school reggae, dudes playing dominoes, the stairs full of estate lads selling hash. We used it as our unofficial off-licence for take-out beers when everywhere else was shut.

Devious D had Bryan G, Jumping Jack Frost, Nicky Blackmarket, Randall, Roni Size. MC Crystalize & Trigga (Manchester), Bassman (Birmingham), Spyda (Nottingham). It was tropically hot in there but somehow everyone kept their black puffer jackets on.

People used to dance with their lighters held aloft, and some crazies would bring aerosols (hair spray & suchlike) to light up like flamethrowers. When you see kids at DNB raves today pulling ‘screw-face’ expressions and raising a ‘gun-finger salute’ in those days the guns were real. There might be an appreciative peal of actual gunfire.

One girl, who was upstairs at the time, got shot in the foot when a gun was fired into the ceiling in the room below. London DJs, unfamiliar to being celebrated in this manner, would duck down behind the decks!

Al Baker Photography

Marcus Intalex

Let’s talk about Marcus Intalex — and Soul:ution at Band on the Wall.

What did those nights mean to Manchester — and what did Marcus represent to you personally, as someone documenting the culture?

Marcus was a lovely guy. A bit of a maverick, he went against the grain. He knew what he liked, what he wanted from his night & for his label. Both had musical identity, integrity and quality. He stuck to his own template.

I was invited to photograph Soul:ution by Gawain at Band On The Wall. I thought Calibre was an amazing producer & DJ. Soul:ution was much more melodic, tuneful & tasteful than some other harder-hitting DNB nights. The atmosphere was great and you saw the same faces in the crowd month after month.

Marcus never booked guests who had ‘the big new tune’ out, he only booked what his own taste dictated. And he had very good taste. When he passed away Fabio did a fantastic radio show in his honour. As the show progressed it moved from unbelievable shock and sadness to ever funnier and more irreverent stories. He’d have appreciated that.

Marcus Intalex and DJ Marky. Soul:ution, Band On The Wall, Manchester

Loss and gain

Looking back now — Hulme is gone, venues have changed, cameras are everywhere — what do you think Manchester has lost, and what has it gained?

One thing Manchester has lost due to its regeneration is space for art to grow organically. Warehouse Project puts on massive festival line-ups, all the big names, but it bores me. I’d rather be in some dingy basement listening to what some kids have just cooked up. Where are the spaces now where young people can set up a recording studio, put on their own parties? We had derelict spaces, abandoned warehouses, flats no-one wanted. We didn’t need (or ever ask for) permission. We just did what we wanted to.

In 1998, as I was looking for something new to photograph, an actor mate was working on an ice-cream truck. He said to me “You wanna come out on the round with me. No-one ever comes to the van without a smile on their face.” I thought that was just perfect. So one day we jumped in the van with my camera & a few rolls of film and we drove around Salford estates selling ice-cream and taking photos of all the kids. These days you’d get lynched for that! I exhibited the photos and got a bit of local media coverage as it was quite a fun project. I was interviewed by Manchester Evening News and the first question they asked was “How on earth did you manage to get permission to do this?” I didn’t. I just did it. Hulme taught me that. Don’t ask, someone will only say ‘no’. Just get on with it.

Ice Cream You Scream (ii), Salford 1998

What were you documenting?

When you look back at this huge archive — decades of work — what do you feel you’ve actually been documenting? Is it the city, the culture, or your own life?

That’s a very good question. I did a talk on my photography a few years ago at UCLAN in Preston, an all-day symposium on documentary photography. I’d always thought of myself in that tradition: 1930s street photographers in Paris, war photographers, social documentary, that was the photography I loved. The night club & Hulme housing estate were my war zone.

But a funny thing happened. While I was showing my photos, telling the stories around them, I saw my own life. I didn’t see the lives of other people. I suddenly saw these photos (that I thought I knew well) as self-portraits that I wasn’t present in. I had decided what to point the camera at, whatever I’d found interesting. I decided when to press the shutter, when to put the camera away. Every image I’d ever made was about me, I guess they always were.

Manchester didn’t just change — it was witnessed. Al Baker’s archive doesn’t romanticise the past or argue with the present; it simply shows what was there, who showed up, and how culture moved through the city before anyone thought to preserve it properly. These photographs remain — not as nostalgia, but as evidence.

Alongside this main feature, Conduct members can access additional unseen images and extended reflections from Al Baker, expanding on moments, places, and stories that couldn’t fit here. Join Conduct to explore the deeper archive and continue documenting underground culture from the inside.